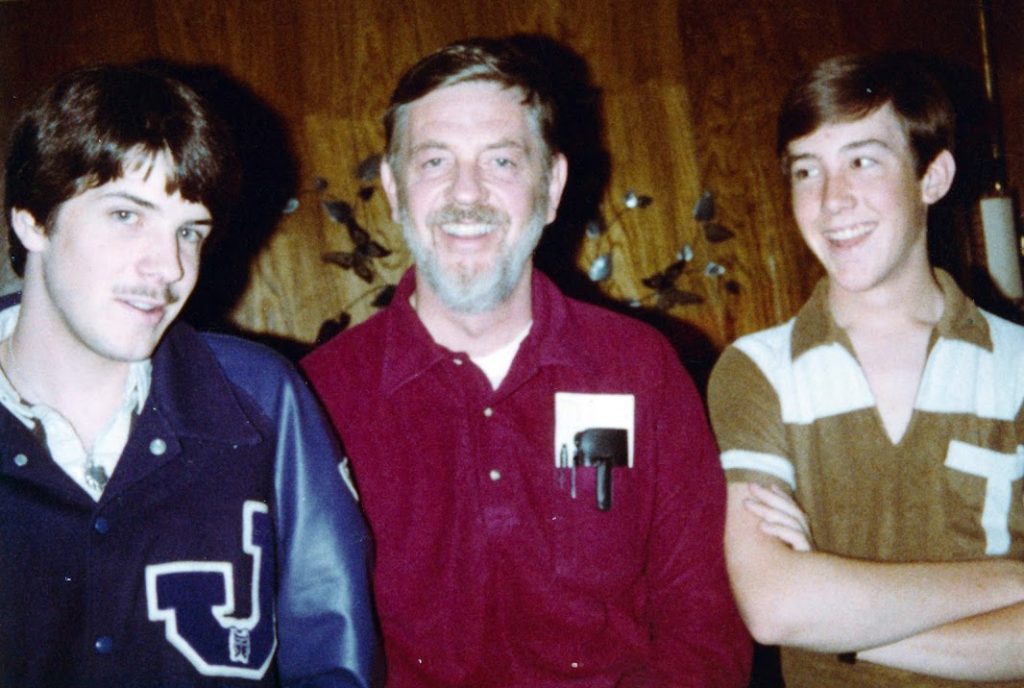

Making decisions for Dad feels strange because he always knew just what to do, and would not hear otherwise. Dad’s opinions were always clear to us, if not always directly stated. In this way, as many others, I guess I resemble him.

My brother and I knew well “the look” you’d get in company that told you to stop whatever you were doing. Now. Dad did not appreciate anyone bragging or drawing too much attention to oneself. He didn’t tolerate us being rude. He didn’t like conflict. If he disagreed with someone we could tell by his face, but it was understood we would not discuss it until afterwards, privately. He kept his differences of opinion to himself. And as kids it was clear we were not to contradict him.

Dad was a classic libertarian, open minded about people’s lives, but wanting the government out of his business. Skeptical of unions, he loved IBM, which rewarded loyalty, took care of its people, promoted from within. Afraid the economy could tank, he invested in gold, stockpiled nonperishable food. He and the second amendment stood ready to defend us should law and order fall apart.

Emergency food preparation and “end of the economy” gold felt scary when I was young, then it seemed like an overreaction as I grew older. But it’s all context I guess. He gave up storing food long ago, but this would have been the year that would have made his plans seem like genius preparation. Believe me, I would be happily reconstituting some of that freeze dried food right now if we had it.

The past 5 or 6 years his opinions have become less pronounced. At first I thought we’d reached a detente because he realized I’d never become a Libertarian and I knew he’d never become a Liberal Democrat.

Then I realized it was opinions that had became less important to him. Everything, from what I could tell, was becoming less urgent and less real to him. He would focus on just one thing, with a narrower and narrower view. Sometimes in the last year only the texture of a tablecloth, or the lights out a window, would hold his attention. Other times he’d see me, and know I was his son. Or at least see me with a friendly gaze.

Increasingly, we have had to make decisions for him, about what food he’d like or what he wants to do. Sometimes he’ll still have strong opinions, and nobody can stonewall like my Dad; if he doesn’t want to go, he’s not going. But increasingly he’s leaving it to the rest of us.

Thankfully we moved him into a memory care place in February, where he gets wonderful fulltime attention and is just one building over from my stepmom Mary. I worried taking care of him had been too much for Mary for years, and it was only getting harder.

Now the buildings are on lockdown, so she and my brother in Austin are as far away from Dad as I am; that is, they cannot see him, and might as well be 1,700 miles away too. He no longer speaks on the phone, but I can call the nurses, get a sense of how he is any given day. Occasionally I send flowers to the wing, which I’m not sure he specifically enjoys, but hopefully it brightens things for everyone at this strange time.

I’m eager, when things are safe enough, for his place to open up, so I can get direct reports from family, and go see him myself.

But this month I’m turning to paperwork, filling in his date of birth and details, trying to sort out things with insurance, Social Security. Not long ago he might not have appreciated me being in his business, certainly wouldn’t have liked that I was spending so much time on him. What’s all this fuss? But now he often doesn’t seem to notice one way or another.

Helping make decisions for someone who once knew exactly how everything should be done is daunting. But being his son, it’s familiar too. I only hope he’d agree, if he knew, that I’m going about it in just the right way.